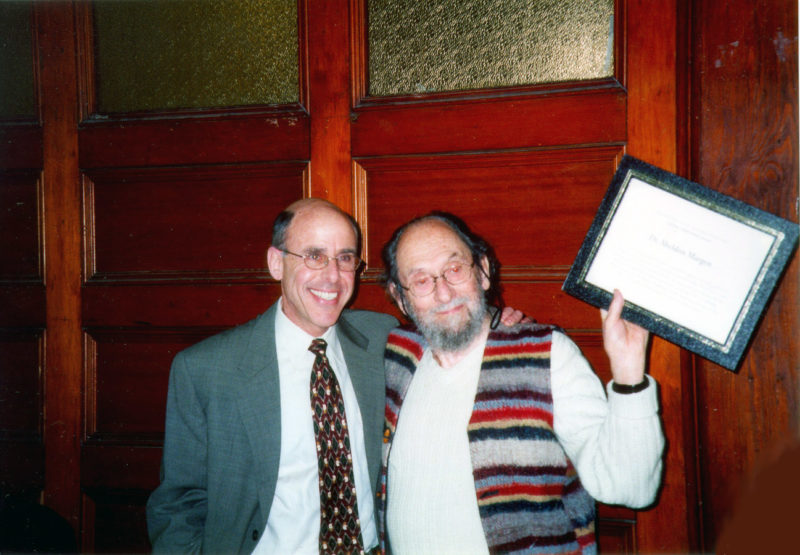

The founding editorial board for The Wellness Letter in University Hall in the early 1990s. Managing editor Dale Ogar, publisher Rodney Friedman, professor and editorial board chair Sheldon Margen, and Dean Emerita Joyce Lashof

The founding editorial board for The Wellness Letter in University Hall in the early 1990s. Managing editor Dale Ogar, publisher Rodney Friedman, professor and editorial board chair Sheldon Margen, and Dean Emerita Joyce Lashof

In October 1984, the first edition of The UC Berkeley Wellness Letter gave its readers a guide to picking out a pair of running shoes, the science of Nicorette gum, advice on selecting and storing tofu, and other lifestyle tips pertaining to health—packaged in an eight-page printed newsletter. Two years of thought and planning by UC Berkeley faculty and staff went into the newsletter’s inauguration. And despite the lengthy planning process, some members of the faculty were worried they’d run out of things to say after a few monthly issues.

“It turned out, we just never ran out of things to say,” says Dale Ogar, a UC Berkeley School of Public Health staff member who has served as managing editor of The Wellness Letter for the entirety of its nearly 35-year run.

If anything, in the ensuing three decades, the writers and editors behind The Wellness Letter had even more myths to debunk and misinformation to address. “If you tend to get your health information from the headlines, you’re very likely to be misled,” says Ogar. Today, a surplus of unvetted material of varying quality and veracity is just a Google search away. No matter what the internet or headlines might say, The Wellness Letter has said from its inception that there are no miracle foods or pills. Only lifestyle changes, everyday ways to look out for our health and wellness.

Since that 1984 issue, The Wellness Letter has brought information to the public focused on the preventative side of health, emphasizing areas of our well-being not limited to medical treatment. Diet and nutrition plans, healthy recipes, fitness guides, stress and mental health tips. The latest science informs these articles, which are then vetted by an editorial board comprised of faculty from the School of Public Health, plus health professionals from UCSF and the Bay Area medical community.

Oftentimes, that vetted information goes against the grain of popular belief of the time. For example, issues of The Wellness Letter have reported that coffee might actually be good for our health. And vitamin C pills don’t prevent colds or cancer.

But debunking health myths and informing the public serves only half the purpose of The Wellness Letter. The other half pertains to the students. “The mission from the beginning has been to bring the public well-vetted information,” says John Swartzberg MD, FACP, professor emeritus and chair of the editorial board. “And at the same time, revenues go to the students to support their education.”

In its more than three decades, The Wellness Letter has earned millions of dollars in subscription revenues that have helped the School of Public Health support students, while providing its evidence-based information to the public. “It’s a win-win,” says Swartzberg. “It has helped us train more public health professionals while at the same time getting good information out to the public about their health.”

Today, the School publishes 16 issues of The Wellness Letter each year along with 16 issues of Health After 50—a newsletter that has a greater focus on medical conditions and treatment—and a catalogue of annual white papers and reports on different health and medical topics. Altogether this content is called Health & Wellness Publications. Through its long-time publishing partner, Remedy Health, some of the content is now also delivered online to the public through BerkeleyWellness.com. Recently, a new partnership with ConnectWell makes the content available through the digital platforms of employers and health providers.

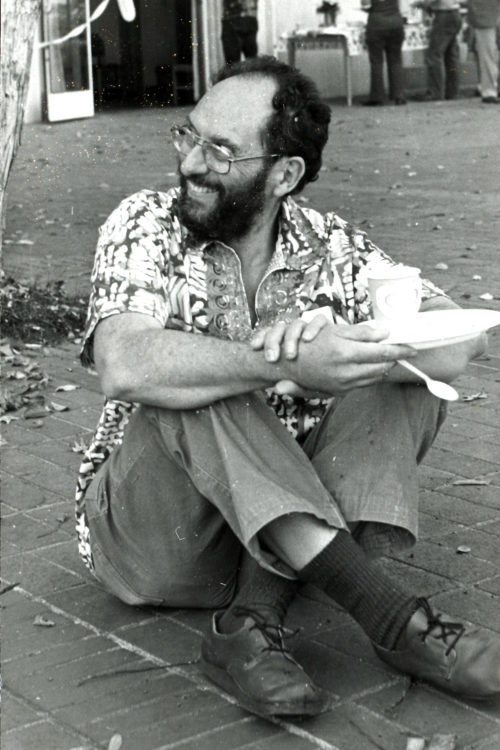

The Wellness Letter started with a phone call between Rodney Friedman and Sheldon Margen in 1982.

At that time, one of the more widely circulated health newsletters came from Harvard Medical School, giving its readership information from its faculty of medical professionals. But Friedman, a New York City publisher, thought there were gaps. He wanted to deliver to readers a perspective on healthcare that wasn’t strictly medical — one that would complement the advice we receive from doctors. So he looked to the field of public health. And, turning the largely East-Coast-based health newsletter market on its head, he looked to the west.

He called Margen, professor at the UC Berkeley School of Public Health and head of its nutrition program.

By that time, Margen had already established himself as an expert on the long-term effects of diet on human health. Starting in 1962 as a professor in the Department of Nutritional Sciences, he carried out a series of landmark studies that significantly informed the U.S. dietary recommendations that show up even today on food labels. Even before that, he practiced medicine and served in World War II as a doctor, treating soldiers and helping to establish feeding regimens for returning prisoners of war. Throughout his career, he was known to have a photographic memory and a close relationship with the library stacks.

“On top of all that, he cared so deeply about people,” says Ogar, who worked closely with Margen for more than thirty years. Ogar believes that Margen’s compassion and intelligence gave The Wellness Letter much of its life in those early years. “He was probably the best friend I ever had in my entire life. I feel a strong need to carry on his legacy.”

“We completely exceeded the expectations that anybody had for this.”

But if Margen brought the mind and heart to The Wellness Letter, Friedman brought its charisma. When Ogar, Margen, and then-dean of the School of Public Health Joyce Lashof, met with Friedman for the first time in person, Friedman showed up in shorts and rollerblades, with a backpack slung over his shoulder. Ogar recalls that his enthusiasm was contagious. He came up with the idea to use the word ‘wellness,’ which had seldom been used in a mainstream healthcare context before.

At that meeting, the idea of the UC Berkeley Wellness Letter was born.

It took time and many faculty meetings for Margen, Ogar, and Lashof to convince the School faculty that a private-public partnership would not compromise the integrity of the School. But Lashof assured the faculty that the information would be evidence-based and personally vetted by her and the editorial board, free from the editorial influences of advertisers and donors. And most importantly of all, the royalties would benefit public health students.

From the publication of the first newsletter, The Wellness Letter moved at full steam, eventually becoming a household direct mail newsletter for many people across the United States and beyond. By 1988, it had the most subscribers of any newsletter in the country, and a few years later circulation had exceeded one million. Ogar estimated that each issue at that time was read by at least two million individuals. They also published 11 books, including several cookbooks, home health encyclopedias, and other hardcover volumes related to health.

“We completely exceeded the expectations that anybody had for this,” says Ogar.

But time and technology brought change to The Wellness Letter, even if its mission has remained constant.

At the turn of the century, Margen’s health began to fail. In 2001, he passed the reins of the editorial board to Swartzberg, who had been working as a member of the editorial board for the newsletter since 1995. Swartzberg has been chair of the editorial board ever since and has had to maneuver The Wellness Letter through several tricky transitions. A few days before Christmas in 2004, Margen passed away after a two-year fight with cancer.

Just two years later, Friedman also conceded to cancer, at the young age of 59. His estate sold his company to another publishing house called Medizine, which later became Remedy Health.

“Over a period of 35 years, there’s been so much change in the ways that people consume information and in the way that people behave in relation to health. One of the biggest challenges is how do you stay relevant?”

Subscription numbers declined steadily, even as printing and mailing costs soared. As Ogar explains, “The downward trend of The Wellness Letter in those years was really a function of the internet more than anything else.”

The heyday of printed subscription-based newsletters yielded to the era of the world wide web, where people expect content free of charge. In response, Remedy Health, led by CEO Mike Cunnion, worked with Swartzberg and Ogar to create BerkeleyWellness.com, an online outlet for some of the information published each month by The Wellness Letter.

“Over a period of 35 years, there’s been so much change in the ways that people consume information and in the way that people behave in relation to health,” said Cunnion. “One of the biggest challenges is how do you stay relevant? How do you evolve as consumer behavior and media changes?”

Through Berkeley Wellness, the Wellness Letter gained a digital footprint and future. And, says Cunnion, “we’re just getting started.”

“We look at it as an important responsibility to make sure it has a future 30 years from now,” said Cunnion. “It’s a daunting challenge because of the way people consume media and pay for media will constantly change, but if there’s a value-centered product that is beautifully expressed—which the Wellness Letter has been for decades—then there will be a bright future.”

In 2017, Remedy Health gifted to the School complete ownership of The Wellness Letter, along with a whole catalogue of annual white papers and the aforementioned newsletter called Health After 50, which had previously been published by Johns Hopkins University. Altogether, these Health & Wellness Publications continue with the same mission as the Wellness Letter of 1984. This ownership agreement has allowed for new marketing efforts, and the circulation of both newsletters and the ancillary publications is now back on the rise. Subscription numbers for both publications have increased by about 25 percent in the last year.

Even more recently, the School of Public Health has launched a partnership with Bay-Area-based ConnectWell to help bring The Health & Wellness Publications to another audience. ConnectWell was founded in 2010 by UC Berkeley alumna Andrea Bloom, who had been a subscriber to The Wellness Letter since 1993. She has nearly 25 years’ experience working in the healthcare industry, where she noticed the lack of sound self-care information available to herself and her colleagues.

“With all of these experiences, I could see more broadly what needed to change in our system,” says Bloom. “We needed to have wellness programing as a complement to healthcare services and healthcare benefits.”

The ConnectWell partnership puts all the School’s wellness content—The Wellness Letter, Health After 50, Wellness Reports, and the white papers—into an easily navigable online library and makes that content available to companies interested in providing vetted preventative health information to their employees.

This partnership builds on the efforts by Swartzberg’s editorial board to deliver the Health & Wellness Publications to more people in more communities, not only across the country but also across the world.

Teh-wei Hu PhD, professor emeritus at the School of Public Health and member of the editorial board, vets Mandarin translations of certain articles in The Wellness Letter published in a periodical in Taipei, Taiwan, as well as in The World Journal, the largest Chinese-language newspaper published in the United States.

In partnership with the Transamerica Center for Health Studies, the Health & Wellness editorial board is also in the process of packaging a version of selected articles in Spanish. They plan to share a free article every other month to start, on topics relevant to the Latino community such as blood pressure and diabetes.

“There’s so little Spanish language health information out there,” says Hector De La Torre, executive director of the Transamerica Center for Health Studies, a nonprofit dedicated to researching health care issues facing employers and consumers today. “We hope to help provide basic, important information to the general population.”

Through both the digital manifestation and language translations of the Health & Wellness content, readers can expect the scale of The Wellness Letter to change, but not its integrity.

As Ogar sees it, if the Health & Wellness Publications continues to build on the legacy of the two men—Margen and Friedman—who laid out its foundation, then the mission of The Wellness Letter will live on to support students and deliver evidence-based information, giving readers a much better sense of how they can take control of their health.

“That is, after all, the mission of the School of Public Health,” said Ogar, even if that mission means using science to say that it’s okay to drink coffee and eat dark chocolate, particularly when the latter may have connections to brain cognition. As the writers at The Wellness Letter often say, moderation is the key.